Danez Smith

Danez Smith

Button Poetry / Exploding Pinecone Press ($12)

by Mary Austin Speaker

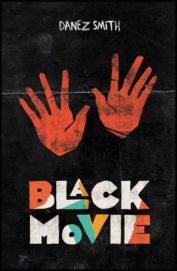

Danez Smith’s Black Movie is a cinematic tour-de-force that lets poetry vie with film for the honor of which medium can most effectively articulate the experience of Black America. Its cover, designed by Nikki Clark, resembles a Spike Lee movie poster, with a bold color palette, chunky, hand-painted lettering, and an illustration of two red hands in the style of Saul Bass. The book takes an unflinching look at how Black Americans have been portrayed in film, and in doing so posits, initially, film as the ultimate myth-making tool of our era. Using this as its jumping-off point, Smith catalogs, in lyric poems that range from the fragment to the prose poem, how filmic myths exist in tension with the real life of Black Americans—the book’s epigraph from filmmaker John Singleton, director of Boyz in the Hood, makes this point of view clear from the outset: “Because, if I’m honest, people in the white world might be appalled, but in the black world, they’re making myths out of me. And I know that ain’t the life.”

Smith’s filmic catalog begins with a series of poetic riffs on Singleton’s cult classic with titles like “Sleeping Beauty in the Hood,” “A History of Violence in the Hood,” and the memorably metaphoric “The Secret Garden in the Hood (or what happens to dead kids when the dirt does its work),” which poses dead Black teens and tweens as the plant life that rises after their bodies are taken into the ground. Each of these poems inserts tragedy where we expect drama but doesn’t use this technique long enough to wear it out. Instead, Smith shifts gears, providing us with the chapbook’s second act—the book’s most devastating poem, “Short Film,” which offers, episodically, and elegiacally, the short stories of the deaths of Black Americans, all of them shot, unarmed, by fearful white people. The poem is interrupted by a gorgeously written section entitled “who has time for joy?” that feels like the heart of the book, the moment when the fourth wall falls away and the writer speaks directly to us: “reader, what does it / feel like to be safe? white? / / how does it feel / to dance when you’re not / / dancing away the ghost?” Whether the reader is white or Black changes the valence of the poem— she is either being offered one of today’s most provocative questions (what does whiteness feel like?) or she is being offered a moment of empathetic pathos, a question relentlessly shared by the Black community: what does it feel like to feel safe? By placing this section in the center of a poem full of true stories, Smith deftly prepares his reader to receive such stark stanzas as “I have no more / room for grief / / for it is everywhere now” and “prediction: the cop will walk free / the boy will still be dead.” This is the fact that rests most brutally in the maw of Black Movie: the just ending we moviegoers seek is not available to the Black Americans who die at the hands of police, regardless of evidence, videotape, or eyewitness account.

So Smith turns instead to poetry, but wrestles with the circumstantial position of the Black poet as the de facto writer of elegies in the thought-provoking “Politics of Elegy” (“raise your hands if you think I’m a messenger. now this time / if you think I’m a tomb raider”). Smith refuses simply to mourn the dead, however, a few pages later, he instead takes a page from Li’l Wayne and posits alienation as a kind of extraterrestrialism in the prose poem “Dear White America,” which announces,

I’ve left Earth to find a place where my kin can be safe, where black people ain’t but people the same color as the good, wet earth, until that means something & until then I bid you well, I bid you war, I bid you our lives to gamble with no more. I’ve left Earth & I am touching everything you beg your telescopes to show you.

This world’s rules are too white to sustain us, Smith tells us, and yet, art continues to be made, poems are written, joy occurs, despite everything. In “Notes for a Film on Black Joy,” a powerful second-person prose poem, Smith catalogues in the gorgeously intimate vernacular of interior thought-language such tender, private moments as watching his mother dancing “so ungospel you wonder if this is what they mean by sin,” praising the abundance of his grandmother’s meat freezer, and the summer he comes into his own as a gay black man—“boys look at you & go blind—most with rage, some with hunger.” It’s here Smith makes his case for raising the unkillable, beautiful parts of Black life to the mythic status of Boyz in the Hood.

The ultimate poem, “Dinosaurs in the Hood,” skewers every trope of Black cinema while offering a fantasy that lets the heroes and heroines of everyday Black life step into the heroic roles of movies: “I want grandmas on the front porch taking out / raptors with guns they hid in walls & under mattresses. . . . I want Cecily Tyson to make a speech.” But the poem doubles back on itself, painfully aware of the likelihood for a film set in a Black neighborhood to be relegated to the sidelines, ghettoized like much of Black experience. Smith resists such relegation, but his placing it in the poem serves to articulate the double-bind of Black hope: the world is too white to sustain a flourishing Blackness, and yet the Black artist must pit himself against it anyhow, planting seed after seed in the form of new poems, new films, new ideas. I hope, sincerely, that film will someday catch up to Smith’s dream. Until then, we have poetry.