by Kevin Brown

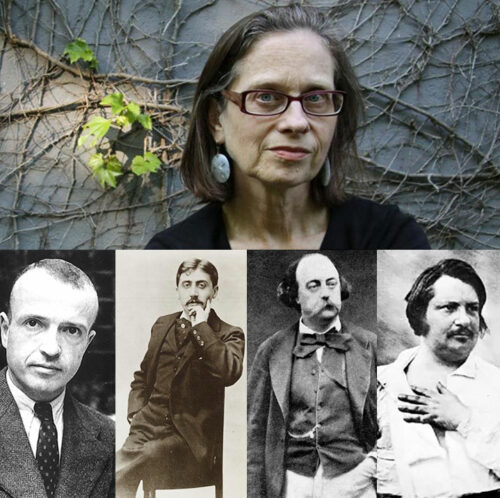

Five books by authors ranging from Balzac to Michel Leiris, three of them translated by Lydia Davis, can be used to understand centuries of French literature and history. One could argue that not only Michel Leiris, but Marcel Proust, Gustave Flaubert, Honoré de Balzac, and ultimately Davis herself, are all quasi-ethnographers possessed of a grasp of both how society works and a sufficient distance to view it objectively. They are able to then write about it from both on high (le monde) and down low (le demi-monde) yet stand at a sufficient remove to retain what translator Raymond N. MacKenzie calls “a clear-sightedness that is almost but not quite cynicism.” This essay examines the evolution of this insight into French culture through some of literature’s most gifted contributors.

I

Brisées: Michel Leiris at 100

One of several Leiris titles Davis translated over thirty years, Brisées: Broken Branches (Northpoint Press) is a gathering of art catalogue essays, reviews, letters to the editor, meditations on the body human and politic, and other occasional personal pieces. Brisées connects to the musculature of Leiris’s overall body of work the way Swann’s Way, Madame Bovary, Lost Illusions, and Lost Souls connect to the skeletal system of French literature. In his 2020 New Yorker article on Leiris, Sasha Frere-Jones notes there are books that “are fully intelligible only as part of the project of a life.” Brisées, like Davis’s Essays, is among them. The groundwork Davis laid translating Leiris’s essays prepared her for what might seem the “pinnacle” of her career as translator—rendering Proust—but counter-intuitive as it may sound, Davis says “the less popular Leiris,” not Proust, may in fact be, “stylistically more intricate and daunting.”

There’s a rational explanation. Like Proust, Leiris is saddled with an “unshakeable and undeserved reputation” for being difficult. During the drafting of his account of an expedition from Dakar to Djibouti (translated by Brent Hayes Edwards as Phantom Africa, Seagull Books, 2019) and thereafter, Leiris developed his books using the old index-card system, jotting down aches and pains, bits of fact, memories, dreams, reflections, lines of lineated verse, prose-poetry, and other scraps. Leiris’s “Cartesian Self” wrote by what he called “fits and starts and without regard for spatial or temporal unities.” To put it surrealistically, they’re like hypnagogic journal-entries, as if painted by Yves Tanguy, a poésie brut documenting the chiaroscuro of the unconscious “in the full light of midday.” Some of Leiris’s essays are as short as one paragraph, a page or two, leaning heavily on metaphor rather than exposition or argument. They sometimes communicate “by way of allusion, analogy, evoking an image.” Davis’s description of Rimbaud’s prose can also be said of Leiris: “A wealth of images . . . develops by leaps of immediate personal association rather than by sequential or narrative logic.”

Leiris excels at physical description. He watches writers, painters, composers like Erik Satie, Joan Miró, and Aimée Césaire. Giacometti’s drawings, engravings, etchings, paintings, and sculptures inspire some of Leiris’s most distinctive writing. And part of what makes Davis such a good translator is disappearing into her role, or seeming to. Adhering to the French tradition of “clear and exact prose,” Davis articulates Leiris’s ideas in such a way that they seldom seem “unnecessarily abstract and obtuse.” Such transparency means the reader isn’t peering over Davis’s shoulder as she translates Leiris, or peering over Leiris’s shoulder as he writes about Giacometti; the reader is standing alongside Giacometti himself, with his “crown of wooly hair,” as he agonizes—merde!—over a figure-study of “isolation and inertia,” the pinched-clay pockmarks and bored-in eyes of a miniature head perched atop “sad stylites.”

Leiris came to manhood as Proust was dying. It’s as true of Leiris’s essays as it is of Proust’s fiction that both are best understood in terms of deep thinking rather than mere phraseology. What Leiris calls “the Proustian illumination,” a certain train of thought, can only be elucidated during unavoidably long hours of concentrated drafting. Leiris is sometimes saying not very novel things but in utterly novel ways. Once you’ve read himon authors such as Paul Eluard, the poet of love in time of war, whose Letters to Gala (published in Jesse Browner’s translation by Paragon House, 1989) is a firsthand account of the Surrealist movement, for example, or pivotal 19th-century predecessors like Rimbaud, who influenced that movement—it becomes clear Leiris is, like Proust, a demanding but not especially “difficult” writer.

The Leirisian sentence, tied in stubborn knots of clause and subclause, reflects contradictions in the man himself. On meeting him, Davis thought Leiris compartmentalized, which seems mirrored in his prose. His person, shesays, was “tailored, spotless.” From getting on the number 63 bus near his apartment to getting off near the gardens of the Trocadéro, Leiris smokes a cigarette and trumpets into his handkerchief, lost in the fugue-state of his own thought, past the point where “a mode of shared understanding” can follow “our private meditations.”

Every author, says Leiris, is “the historiographer of his own themes.” His training as an ethnographer placed Leiris in the perhaps impossible “position of impartial observer, detached from the system of values [one] inherits from [one’s] own culture and likewise detached from the cultures [one] studies.” Ethnography allowed him to form “a concrete view of . . . the social minimum that defines the human condition.” But it washis taste for poetry that led Leiris to ethnography, not the other way around. The self-begetting essays in Brisées range from a lecture on Haitian voodoo priests to prose-arias of minotauromachy before coming back to ethnographic contributions to French journals on the syncretism between African spirits and Catholic saints. Davis says “Leiris’s project was to take himself as subject, with a sort of ethnographic objectivity, and write himself into being, to arrive at a sense of himself and how best to conduct his life, through the years-long, intensive labor of exploring himself through writing.”

Readers shouldn’t expect Brisées to wind itself seamlessly around a central theme. The “Ariadne thread” tying these essays together is Leiris’s effort to follow the many aspects of art as one whole—the circus clowns of Picasso’s Rose Period, dance, music, theater—in order to “arrive at a complete view of man encompassing his twofold existence as a product of culture and a fragment of nature.”

II

Swann's Way: Proust at 150

Proust was about thirty when Leiris was born; by 1909, he’d arrived at the mature style we now call “Proustian.” Swann’s Way (Penguin Classics, $20) tells two related yet distinct stories: one involving Marcel, a younger version of our Narrator, the other about Charles Swann, a friend of Marcel’s family. “Swann in Love,” the psychobiography of jealous obsession embedded within, is a novella of manners flashing back to a period 15 years before the narrator was born and continuing through Marcel’s youth at Combray, where his grandparents live and his family visits during holiday vacations. Taxiing down the runway for the first 195 pages, the novel sprouts wings and generates lift, a magic-trick exhilarating to witness. A reader who gets that far may find the rest hard to put down.

Swann’s Way is less daunting when its many modalities and disquisitions—adage, aphorism, apothegm, architecture, art criticism, literary criticism, maxim, music, natural history, portraiture, prose poem, proverb, theater—are thought of as essays in search of a novel. Some have questioned whether in order to achieve hybridity, Proust sacrificed achieving “unity, life.” Whether describing a waterlily, a cathedral façade or the racing of his insomniac thoughts, there’s something of what Davis in another context calls “deliberate overload”—auditory, gustatory-olfactory, tactile, visual—in Proust’s perceptions. Sasha Frere-Jones wrote that, “Leiris doesn’t interpret [a thing] so much as study himself in its presence,” and it’s Leiris who’s most helpful in this context because precisely the same can be said of Proust. “Every observation,” Leiris writes, “is a relationship between someone looking and something looked at.” Oftentimes Proust’s Narrator, insisting that the reader “pay attention to me . . . know me!” is pushing the limits of the communicable past the point of the ineffable. Leiris is making what he calls “a perpetual encroachment of the act of narration on the thing narrated.” Proust doesn’t just toe the line between the all-consuming “I” and the universal “we,” between absorption and self-absorption, between direct or indirect object and almost overwhelming subjectivity, between pitiless scrutiny and self-pity—he crosses it. Proust isn’t so much a “difficult” as an experimental writer, attempting to write as Monet painted or Wagner composed. It’s in the nature of experiments to test failure.

Swann’s Way is full of eccentrics such as Proust. “Like certain novelists,” he “has divided his personality between . . . characters.” Proust is not always Marcel, or vice versa. Asthmatic, noise-sensitive, Marcel has much in common with our Narrator, whom Proust calls “the unconscious author of my sufferings,” but is not necessarily the same person. Likewise, “I began to take an interest in [Swann’s] character,” our Narrator says, “because of the resemblances it offered to my own.” Swann’s eczema, his balding red hair, and patchy beard in no way resemble the features of our androgynous pretty-boy with curl papers in his hair. On the other hand, Swann, “my other self,” is very much like Marcel in that he’s “a shrewd observer of manners.” Marcel’s “studious youth” recalls “the inspirations of [Swann’s] youth, which had been dissipated by a frivolous life.”

Haunted by unfinished works like The Human Comedy, by unrealized talents like that of Swann, Marcel decides to become a writer, to describe faithfully what he sees in nature, art, and society. One day, Marcel dreams, “I would be the foremost writer of the day.” A man of 38 subsisting on croissants and caffeine, Proust spent the last dozen years of his life in search of lost time, reliving it from childhood to his present twilight moment in European civilization. Sometimes in the guise of Marcel, sometimes as Proust himself, our Narrator is writing himself into being.

Passages in Proust are sometimes long, and if it’s been decades since you last read a couple volumes from In Search of, it can take some time to readjust because within “his long sentences, far-fetched comparisons, and over exuberant eloquence,” sometimes very little actually happens. But Proust’s sentences don’t ramble; they are built on solid foundations of syntax and grammar. Whatever problems readers may have with him, mere length shouldn’t be among them. Proust’s storytelling breathes, sometimes shallow and gasping, sometimes deep. But he can be strikingly succinct, and to her credit as translator, Davis can match him for brevity or expansiveness: "He raised himself on his tiptoes. He knocked.”

The “Proustian sentence” isn’t one thing; it’s many things. You might even say, stretching the comparison to absurd lengths, that the Proustian paragraph itself is not a single thing, continuous and indivisible. It is composed of a molecular infinitude of successive sentences, of different sentences, which may in themselves seem ephemera, but by their interrupted multitude give the impression of continuity, the illusion of unity.

That said, a single sentence of Proust’s can go on for an entire paragraph, and that paragraph for several pages sparsely populated with commas unless the author is striving for effect, in which case he may sometimes flat or sharp them like “wrong notes coaxed by unskillful fingers from an out-of-tune piano.” Dialogue is sometimes broken out conventionally, as in a stage play, which permits those pages to go quite quickly. Other times, the dialogue stays within the paragraph. Chapter headings or section breaks are almost non-existent, in contrast to Flaubert or Balzac. This slosh-over effect forbids the reader to put the novel down and conveniently pick up the thread again. The thousand-odd pages of Within a Budding Grove and Swann’s Way, so needful of constant attention, are best suited to uninterrupted stretches of reading on a delivery device other than a smart phone. A reader has two choices: either indulge Proust as he introduces all the characters who will occur, develop, and recur throughout this seven-movement opus, as he introduces all the themes that rhyme with what’s gone before and what’s yet to come; or read something else.

Of course, Proust has his critics, and his critics have a point. Even Davis admits, in a 2006 letter to the editors of the New York Review of Books, that he can be “oppressively overwrought, even saccharine.” Some readers couldn’t care less about the gaffes Marcel commits or about his perhaps excessive disillusionment over the petty snubs of petty snobs who never really deserved all that flattery and fawning he’d lavished on them in the first place. And for some critics, Proust’s vast intellect and powers of observation seem squandered in this “study of the nobility; a Parisian novel; an essay on Sainte-Beuve and Flaubert; an essay on women; and an essay on pederasty.”

Proust’s Narrator shifts back and forth between the necessarily circumscribed “I” of Marcel, the third person “he,” she,” and “they” of “Swann in Love,” and the all-seeing eye of Proust himself and his philosophically generalizing “we” and “our” used in speculative digressions. The points of view get blurred, intentionally or otherwise. It’s hard to tell how and what one character, including Marcel, knew about another, and when that character knew it. Through what he called “retrospective illuminations,” Proust gives his Narrator access to information other characters lack. But the reader also begins to suspect things about Proust that he himself may not have known or wanted known. “Since I wanted to be a writer someday,” our Narrator writes, “it was time to find out what I meant to write.” Even Proust at his death could not have known how self-fulfilling this prophecy would be.

Unless he was gathering material for his great work of recapturing the past, Proust made himself scarce. Perhaps he realized literary genius would never have taken him “very far in society” anyhow. By the time of these reflections, Proust—a shut-in, mostly bed-ridden, like his great-aunt Léonie—mostly came out at night, his complexion ashen and his eyes hollowed out like a Giacometti portrait in monochrome. Even indoors, dining at the Ritz, Proust wore a heavy fur coat over his evening clothes, and evening clothes over his long-johns, refusing to remove his top-hat for fear of worsening his cold, his canals infected by the earplugs he always wore to drown out the neighbors’ noise. “How frightfully ill he’s looking,” people whisper, scandalized.

Proust wasted away to 100 pounds, and was dead, like Balzac, by age fifty-one.

III

The Bride of Yonville: Flaubert at 200

What’s left to say about Madame Bovary (Penguin Classics, $17)? This novelspeaks to Proust’s notion that “the ideal is inaccessible and happiness mediocre.” In order to organize discussion surrounding this much-discussed work, let’s break this section down by act.

— Act One —

We first encounter Emma “in the freshness of her beauty, before the defilement of marriage and the disillusionment of adultery.” One obvious difference between Proust and Flaubert is their respective degrees of authorial intervention. Always intrusive, sometimes hectoring, full of digressions “thickened by a great mass of fustian,” Balzac addresses his reader directly. Meanwhile, Proust’s first-person Narrator passes moral judgments Flaubert’s omniscience does not allow. Flaubert is superb at asynchronous revelation of motive, how characters see one another, and how those same characters see themselves. From a vantage point whose spherical center is everywhere, its circumference nowhere, Flaubert hints by indirection at things the reader’s already beginning to suspect; he shows simultaneously the lies people tell each other, and the half-truths they keep from themselves.

Père Rouault, Emma’s father, offers Charles Bovary the consolations of philosophy to help him get over the grief he feels when his first wife dies. Before either the prospective bride or groom see it coming, cunning meets guilelessness as Rouault calculates how to dower Emma off to Charles, the way a farmer might auction off a less-than-prize heifer to a witless buyer. (Flaubert describes her teeth, as if she were a fine specimen trotted out among dung at a county fair, not just as “pearly” but “nacreous.” The old master practically railroads poor Bovary into the marriage arrangement.

By the morning after the big wedding day, Emma’s already fallen out of love with the reality of a marriage she feels martyred to. She’s married a physician with more than a little Norman peasant in him—he gargles his soup. While Charles is performing his country doctor duties, Emma—with too much time on her hands—passes her days thinking up extravagant names “for a perfectly simple dish that the servant had spoiled.” Emma and Charles: so close in the same bed, so far apart in the same room.

Meanwhile “one day nosed along on the heels of the next.” In Flaubert, as in Proust and Leiris, there’s maximalist “profusion within a frame” of description, as Davis puts it in "The Impetus Was Delight" from Essays One: the touch of a warm wind; the dogs’ volley-barking; white billiard balls caroming over green felt tables; that barnyard smell of a hen laying an egg. Vast amounts of data never seem to retard the narrative momentum of Bovary, however, because Flaubert horsewhips his narrative, foaming and frothing like a thoroughbred. At 350 pages, this booknever once feels drawn out.

Charles falls hard for Emma, as Swann does Odette, but Emma simply cannot “convince herself that the calm life she was living was the happiness of which she had dreamed.” Bored with him, Emma’s already contemplating adultery—though she never seems to admit that to herself. The reader never questions whether she’s going to cheat on Charles, only when and where. It’s a village, for Chrissakes! “Provincial life,” Balzac informs, “is based on a meticulous, detailed system of espionage, insisting that one’s private life be open to everyone’s view at all times.” How’s she supposed to pull off all this mounting and dismounting? And with whom?

— Act Two —

Flaubert’s timing and comic effects sometimes “stupefy the understanding.” One of Davis’s many achievements in translating Bovary is laughter on almost every page. And this is not accidental. She has clearly thought, very carefully, about keeping Flaubert funny. Any translator can tell you that carrying humor over from the source to the “target language” is one of the hardest things to do. Even when Flaubert is drawing your attention elsewhere, you find it impossible to ignore how marvelously well he’s doing it. The pecking orders of cruelty in many of these novels is similar and recognizable. In Proust, Françoise heaps verbal abuse on a Combray servant-girl whom Swann may or may not have impregnated while she is in labor pains; Forcheville tongue-lashes Saniette in front of everybody; Mme. Verdurin humiliates Swann in front of Odette and Forcheville. In Flaubert, the help bully farm animals; masters lord it over the help. Pompous pharmacist Homais is as abusive toward underlings he berates for their “ineducable incompetence,” as Proust calls it, as he is “drawn to those in Power.”

Emma’s disappointment breeds contempt. When Bovary undresses, she complains of a headache. Little by little, she refuses to share the marriage bed at all.

During this petulant depression, everything irks her, not least herself. A creature of moods and whims—now feverish with gaiety, now “drunk with sadness,” now aloof, now explosive with lust—Emma’s a bundle of misdirected energy. She stays up all night reading dirty books and sleeps till four in the afternoon, or else she’s compulsively neat, thrifty as a Picard village housewife, exaggeratedly attentive to her household duties and newborn daughter. Other times she literally can’t be bothered with the drooler. Her pathology sounds vaguely familiar. Leiris, too, suffered from bouts of clinical depression. Within months, Emma’s water-faucet tears, her “exaggerated speeches [concealing] commonplace affections,” are becoming tedious. Even before he’s conquered Emma, Rodolphe’s already plotting how to get rid of her. Boulanger dallies with Emma, smacking her emotions around like a tomcat toying with a half-dead mouse.

Flaubert shares with Proust an attention to detail verging on mania—especially in women’s fashion, for which Emma yearns as lustily as does Odette. For one who inveighs so mightily against the bourgeousie, the Old Rouennais has a gluttonously keen eye for material possessions. Emma lavishes on her much wealthier lover extravagant gifts she can’t possibly afford. She lies, cheats, Ponzi-schemes, goes on shopping sprees. But instead of gratifying, these presents embarrass Rodolphe.

Rodolphe writes Emma a florid letter. Reading it, Emma sprouts three gray hairs and faints dead away, lapsing into a coma; she remains bedridden 43 days. Once awake again, she begins contemplating suicide—an act Leiris attempted via barbiturate overdose. The blue jar on the third shelf in the capharnaum, once mentioned in Act Two, must be emptied by the end of Act Three.

— Act Three —

For Léon, Emma’s final lover, part of her charm as mistress is precisely that she’s a married woman, whereas she herself “was rediscovering in adultery all the platitudes of marriage.” They tire of each other.

After 240 pages, everybody in Yonville knows about Emma’s infidelities except Charles. Even when he finds in the attic a faded love letter to Emma from Rodolphe, Charles convinces himself their “love” must have been platonic. There are many plausible alternate endings. More than one character spells out for her the option obvious in the reader’s mind, a theme common to all four novels under discussion here. But in her own eyes, Emma is much too storybook a heroine for that: “I’m to be pitied, but I’m not for sale!” “Facts,” says Proust, “do not find their way into the world in which our beliefs reside.”

IV

Balzac: Lost Illusions and Lost Souls

If readers in the monoglot “anglosphere” struggle through Proust and Flaubert, where to begin with Balzac’s vast fictional chronicle of France between 1815–1848, The Human Comedy? Two novels recently translated by Raymond N. MacKenzie, Lost Illusions and Lost Souls (University of Minnesota Press, $19.95 each), suggest an answer. Are these 1,066 pages worth the trouble? Unequivocally. To read Balzac, you have to accept him for what he is: a very uneven writer.

Langston Hughes, who might have bussed Leiris’s cabaret table without either knowing, is a recognizably Balzacian “type.” Wealth, like an estranged parent’s withheld affection, shunned Hughes all his life. He churned out plays, opera and oratorio libretti, literary fiction, and newspaper columns under his own name and pulp fiction under pseudonyms. He hustled from book contract to book contract, staying afloat on advances for books not even started much less finished, dodging landlords when the rent was due. The fictional version of this type, recurring in both Lost Illusions and Lost Souls, is poet-dandy Lucien Chardon de Rubempré. A young man from the provinces, he arrived with “the boldness of the social climber,” writes Balzac, and “came to the house [the Faubourg-Saint-Germain] five days out of the week, gracefully swallowed insults from the resentful, tolerated impertinent glares, and made witty responses to mockery.” Lost Illusions, the prequel to Lost Souls, is what MacKenzie calls “the truly foundational text in the vast Comédie, both in its form and its themes,” and might easily have been subtitled “Scenes from Literary Life.”

In some respects, literary life in 1822, the dawn of print media’s ascendancy, seems unchanged from that of our print media twilight in 2022. Media moguls still rely on interns performing “a year’s work for no salary.” What has changed is that the supply of journalists now far exceeds the demand for column inches. Lucien spends his days at the Sainte-Geneviève public library, where it’s drier and better lit than in his unheated garret, working on his first novel and his chapbook. Lucien gets a behind-the-scenes view of how publications are run; how gatekeepers see to it The Paper isn’t overrun by unsolicited contributors. “If you don’t already have a reputation,” one publisher, admiring his own manicure, frankly admits, “I’m not interested.”

Not content to live on bread and milk, Lucien networks. He becomes a theater critic and book reviewer—a “paid assassin” as Balzac puts it, “of literary reputations.” All he need do to get invited to dinner seven nights a week, for actresses to twine themselves around him like a clematis, to become an influencer in France and find a publisher for his own books, is to write witty reviews of other books he may or may not even bother to read, to “attack when [someone] says ‘Attack!’ and praise when [someone] says ‘Praise!’” Lucien’s first theater review is a success. He awakes to find himself famous, flattered, cajoled. Lucien “listened to all their nonsense,” Balzac winks, “and it impressed him, completing his corruption.” Now that he’s a journalist, with a mistress to boot, Lucien gives himself Byronic airs, “staring down the dandies who had mortified him.” “The looks exchanged,” Balzac writes, “were loaded like pistols.”

The problem isn’t that Lucien wants more—his own horse and carriage, a liveried coachman, beautiful surroundings to write in. The problem is that he wastes more time and energy schmoozing at editorial meetings than Swann fritters away at Verdurin soirées. Whereas Balzac, when not gathering material for his stories, was often “unable to come; he was finishing his book.” Lucien’s “as apt to end up hanged,” Balzac prophesizes, “as to make his fortune.” Our poet is doomed, but it takes him two novels to figure that out.

It was trendy in the 1970s to talk about György Lukács, social realism, and Balzac. What strikes a 21st-century reader about those takedowns of Lost Illusions or shakedowns of Lost Souls is their make-believe theatricality. At first, Balzac wrote Gothic potboilers under a pseudonym. These apprentice works had as few readers during the 1820s as his mature works in English probably have now. The odds against winning the genre-fiction lottery are long. Balzac should have known better. But he wagered anyway. Our great man from the provinces gambled and lost money he never lived to repay on failed schemes like politics and the printing business. He resolved to write under his own name the post-Napoleonic era novels we now know him for.

Salon readings, not newspaper serialization, were the way authors like Dumas, Hugo, Lamartine, Musset, and Sand were made known to a wider public. Balzac signed a contract in 1835 for Lost Souls, then tentatively titled “Scenes from Provincial Life.” His deadline was 1836. Working to dash off in twenty days a book that had been gestating in his mind for twelve years, at one point writing feverishly for three days straight, Balzac collapsed from exhaustion. He refocused in November 1836, and finished the project on January 20, 1837. The book went on sale that February and was serialized in French daily newspapers between 1837 and 1843, never on deadline and always over word-count by a writer juggling too many projects on too little sleep. Lost Illusions often bows in the direction of commercial elements that don’t always serve the psychological novel’s High Seriousness.

The University of Minnesota Press editions, usefully footnoted, are clearly intended for classroom use. But Balzac wrote not just for remote posterity, but to escape poverty in the here and now. His works have hot tears of Ivanhoe historical romance vying with dueling pistols at twenty-five paces; they put picaresque lives side by side with twelve-page letters of the epistolary novel that has “love as its subject and musk as its scent, sprinkled with madrigals and metaphors,” which letters are written in feverish haste and purposefully mislaid. Nucingen, the love-sick baron, goes running all over, searching for Esther the way Swann searches for Odette, who cheats on Charles the way Emma cheats on Bovary. Intimate scenes painted on a vast canvas constitute the Novel of Everything.

The world of Lost Souls is “amoral, hypocritical, brazen, dishonest, and murderous.” Much has been made of Balzac’s influence on espionage and crime fiction writers like John le Carré, Dashiell Hammett, and George Simenon. A hundred years after Balzac, writing Casino Royale, Ian Fleming was still complaining that genre fiction in general and spy thrillers in particular were too long, too poorly written, and bullet-riddled with clichés. Maltese Falcon seems almost Flaubertian in comparison. There’s an unavoidable trade-off in character-development for all those scenic locations and all that fast-cut/slow-mo action.

Lost Illusions, at 585 pages, is almost twice as long as Bovary. In places, it feels twice as drawn out. Flaubert admired Balzac despite “the stigma of aesthetic inferiority” Milan Kundera says he labors under. A careful student of Balzac, Proust admits that the Comedy, “magnificently overloaded” with proper names, is hard to track. Literally thousands of characters occur and recur in nearly 100 interconnected short-stories, novellas, and novels. Sometimes these “characters” are just names (“Albertine,” “Proust,” or “Marcel”) you can’t match a face to. There are 273 names in Lost Souls alone, many of them recurrences from previous volumes of the Comedy. Following the money, as Flaubert does, is what readers expect Balzac to do. In both Flaubert and Balzac there are particularized ledger accounts of how much everything costs. Even Proust, a trust-fund writer one might expect to be above such matters, we get a detailed accounting of how Odette’s willingness to have Swann to bail her out of money troubles bonds them together.

It would be better to skip Balzac altogether than to read him as hurriedly as he himself wrote. To a first-time reader I would give this advice: Go to bed early, get lots of sleep, get caffeinated, then machete your way through these thickets of longueurs. The reader who perseveres past the bad puns and maudlin bits will be rewarded, even as their patience is tried. The European federation seemed a wild dream in 1830. When Proust died in 1922, the 19th century we think we know—an era when nobody ate dinner till 10 p.m., servants prepared five-hour luncheons for thirty guests and forty candelabras, and the Bourse didn’t open trading till 3 p.m.—was an era when even Faubourg townhouses didn’t have electricity. One reason Balzac’s depiction of literary life remains so vivid is because that life was his life. Balzac didn’t invent bohemia; he frequented the stalls of used-book vendors along the quays from the Pont Notre-Dame to the Pont Royal, where starving writers like Lucien read books they couldn’t afford to buy. It’s hard to think of a more accurate depiction of it.

Balzac was a storyteller, MacKenzie writes, but much more than that. Balzac’s Comedy was envisioned as “a vast summa.” MacKenzie writes:

Whole family stories emerge across all these works, and the history, politics, and social relations of France are explored and analyzed from what seems like an endless series of varying angles. And allowing the reader to see these numerous characters from different perspectives, sometimes in the background, sometimes in the foreground, and in different situations at different points in their lives, gives them a depth that is unrivaled in fiction.

Peter Brooks thinks Lost Illusions is perhaps Balzac’s greatest novel. MacKenzie calls Lost Souls “one of the most energetic, compulsively readable works in all Balzac’s canon.”

Balzac’s insights into the cultural, economic, political, and social upheavals experienced by a fictional poet in his twenties—the Revolution, the Directorate, the Empire, the Restoration—as seen from the point of view of a novelist in his forties still seem relevant nearly 225 years after his birth. If “the true aim of [great] works is to stimulate ample discussion,” then the great man from the provinces, despite his flaws, is truly great.

French-language writers form a distinct subculture because “culture,” according to Leiris, “defined as the sum of the modes of acting and thinking, all to some degree traditional, peculiar to a more or less complex and more or less extended human group—is inseparable from history.” Leiris at 100 nods to Proust; Proust at 150 nods to Flaubert; and Flaubert at 200 nods to Balzac, born between the six months separating the collapse of the Revolution and 18 Brumaire, Republican Year VII of the French calendar. Each isa chronicler of French society both high (le monde) and low (le demi-monde), a spectator to what Balzac calls the “Theater of National Absurdity” who saw through what Leiris calls “the insanity of the current order of our social relations.”

One’s admiration is unequally divided, to paraphrase Swann, among the four. Leiris’s darkly surrealistic vision of human bodily functions as “organs of excretion” or, by metaphorical extension, of the body politic, of civilization itself, as a city “poisoned by a million sewers” is a vision Balzac would have understood. Lost Souls seems full of the 19th-century equivalent of 20th-century prisons like La Santé, an isosceles trapezoid in the heart of the hex, where the worst of the worst once clogged the eastern heart of the 14th arrondisement; and the capital itself sometimes seems a vast, plein-air penitentiary. Lost Illusions is a story of an idealistic young writer’s swift corruption. Proust’s ambition as novelist was “a desire to write a book that would rival Balzac’s panorama of Parisian society” and to frame within that frame the intimate history of a young man’s artistic and spiritual evolution. Satire in Bovary takes down many targets—windbag politicos, idiotic savants, mock-editorial columnists—with a quiver of energies that seems more sustained than that of the other three novels. Yet Balzac would have been Balzac with or without Flaubert and Proust. Could either Flaubert or Proust have realized himself without Balzac?

What’s the point of arguing whether Davis’s or some other’s translation of Bovary or Proust is “definitive?” There’d been 20 previous translations of Bovary into English alone. Hers is unlikely to be the last. MacKenzie says, “times change, idioms change, audiences change, and so does our sense of what sounds dated and what sounds right, what sounds bookish and what sounds vital.” Davis spent three years translating Bovary, “a complicated mechanism” it took Flaubert four and a half to write. Whatever the durability of her translations, their conscientiousness is beyond question. She puzzled for three decades over just three lines from poet Anselm Hollo. Readers can trust Davis to have erred, when she does err, on the side of what Peter Brooks calls “rigor and exactitude.” From each generation a reading of the classics according to its interpretive ability; to each generation a translation according to its needs.

V

Lydia Davis

MacKenzie warns readers in search of overarching themes in Balzac to seek them only in terms of “a unity of tone, of sensibility, and of outlook rather than plot structure.” The same could be said of Davis’s Essays, perhaps best thought of as collected nonfictions. The thousand or so pages of Essays One (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $23) and Essays Two (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $35) consist of anthology pieces, book reviews of others’ translations, introductions and prefaces to her own book-length projects, lecture series, and seminar and workshop talks. They center around the literary arts, the art of translation, and the visual arts. Because so much has already been said by reviewers pro and con about her versions of Leiris, Proust, and Flaubert, the following remarks are limited to how Davis’s work as translator, as revealed in her collected Essays, has helped her growth as author in her own right.

Davis questions “why one artist will evolve and change within relatively narrow limits while another will move from one expressive form to another.” Apart from her studies with Grace Paley, Davis isn’t a product of writers’ workshops. She’s not really an “academic,” although she teaches. Born as Michel Butor was graduating the Sorbonne, Davis studied German during primary school, Latin and Romance languages like Italian and Spanish later on. Many translators mentioned in her Essays are themselves canonic postwar writers born a generation before she was, or born, in the case of Elizabeth Hardwick, around the time Proust published Swann’s Way (1913). Some taught at institutions that shaped the thought of her generation but passed away around the time Davis’s earliest essays began pooling in her mind: Ralph Manheim on German-language and Eastern European writers like Peter Handke; William Weaver on Italian literature; Richard Wilbur on 17th-century French dramatists. In qualified retrospect, it seems a golden age of foreign language literature translated into English. By the time Richard Howard translated Mythologies (1972) and other works by Roland Barthes, or Gilles Deleuze’s Proust and Signs, or Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma, Davis had already lived in France. Her earliest essays date from the late ’70s and early ’80s, and reflect the influence of nouveau roman writers like Duras or Robbe-Grillet. By her late twenties, Davis was translating Blanchot.

The careers of Davis and Leiris intersect in many ways, the most obvious of which being that their essays complement their work in other genres. “Some of my work,” Davis admits, “comes right up to the line (if there is one) that separates a piece of prose from a poem, and even crosses it . . .” —something that is also true of Leiris. Visual artists inspire some of Davis’s most distinctive nonfiction in two radically different yet equally convincing essays. Color illustrations help one appreciate how faithfully Davis describes Alan Cote’s paintings without reading unnecessary “metaphorical signification” into them. “The Impetus Was Delight,” Davis’s essay on Joseph Cornell, strikes a balance between what she, the receptor, is seeing and what an auditor, the reader, is hearing. Even when you know the provenance of that essay is the multi-genre anthology A Convergence of Birds (edited by Jonathan Safran Foer and published by D.A.P., 2001), the question of whether the piece is fiction or nonfiction, non-lineated poetry or a prose poem seems moot. Hybridity being at the heart of what she is, Davis doesn’t really need a label. So why not call her a writer of “imaginative prose,” and leave it at that?

Davis does so many little things right most readers couldn’t or shouldn’t even notice. She takes pride in her own writing, but clearly wants these translations to last. Her submission to the text is such that Leiris in English does not sound like Proust or Flaubert. And each sounds very different from the Lydia Davis of Essays One and Two. At age 75, Lydia Davis has achieved something even more remarkable than a large and varied body of work: She has written herself into being.

Click links to purchase books discussed in this essay at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2022 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2022